Who do you really work for?

It seems like an obvious question, but it’s one that the Department of Labor has struggled to answer for years.

An epidemic of employee misclassification has struck at the heart of American employment, leaving thousands of workers in a legal gray area. Companies big and small have been mislabeling their employees as “independent contractors” for decades. But a new generation of “sharing economy” companies like Uber and Caviar have made nailing down the definition of independent contractors more important than ever.

Employers who misclassify their workers get rich off lower taxes, while true employees lose out on the minimum wage and overtime pay protections guaranteed by the Fair Labor Standards Act.

That’s all about to change.

Am I An FLSA Exempt Independent Contractor?

Probably not.

A new Department of Labor guidance, Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2015-1, has significantly expanded the definition of “employee,” and restricted the category of “independent contractor,” meaning most people who work will now be definitively classified as employees.

That means a fair wage, and guaranteed overtime pay, for more workers than ever before.

But there will still be independent contractors, just nowhere near as many. And with “employee” status guaranteeing you at least $7.25 per hour and time-and-a-half for hours worked over 40, it’s never been more important to understand what an independent contractor is, and what it’s not.

Independent Contractor Vs. Employee: The Basics

The DOL’s new guidance on distinguishing between an employee and an independent contractor comes down to one thing: real economic independence.

The basic question to ask is whether you’re economically dependent on your employer and their business or are you effectively self-employed, are you in business for yourself?

Rejecting Control: The Fair Labor Standards Act’s Definition Of “Employment”

Before 1947, accurately calling someone an independent contractor was a matter of “control.”

Under this common law theory, employers tell employees what to do, when and where to do it and how. Their employment activities are effectively “controlled” by the employer.

Working relationships that didn’t fit into that mold were between clients and independent contractors.

But in drafting the Fair Labor Standards Act, Congress rejected the “control” model of employment. As passed in 1947, the law used a much broader definition: an employee was anyone that an employer “suffered or permitted to work.”

What Does “Suffer Or Permit To Work” Mean?

According to the Department of Labor, “suffer or permit to work […] means that if an employer requires or allows employees to work they are employed and the time spent is probably hours worked.”

That “allow” is crucial. Contrary to the “control” doctrine, an employer doesn’t need to tell you exactly what to do, or where to go, for you to be an employee.

For one thing, this definition means that it’s an employer’s burden to make sure that you’re not working overtime if they don’t want you to. But “suffer or permit to work” also informs the DOL’s new instructions on defining employees, simply because it’s so broad. In fact, the definition of employment was designed to be as broad as possible, to cover as many workers under the FLSA’s protections as Congress could.

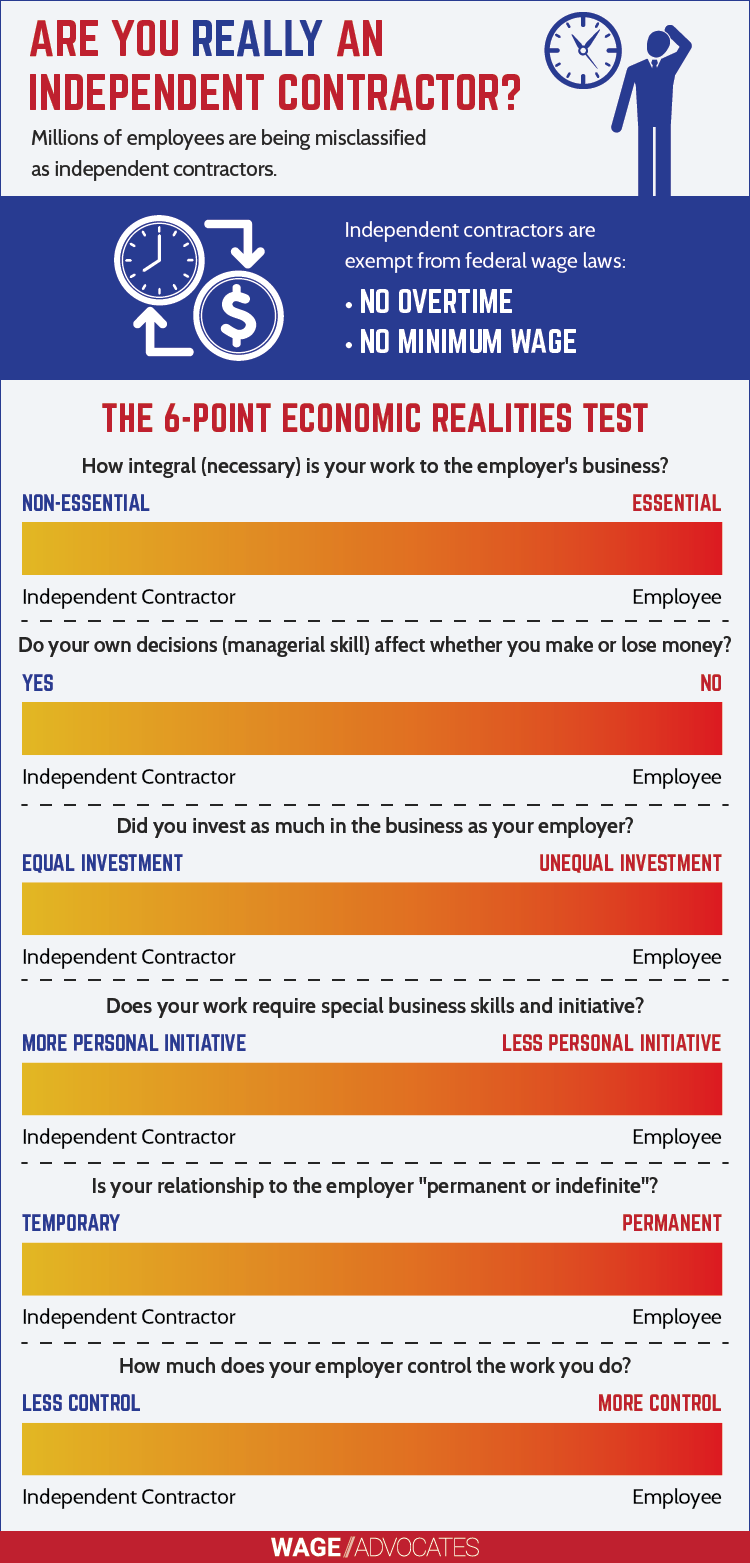

6 Steps To Independence: The “Economic Realities” Test

With this broad definition of employment in mind, we can turn to what really defines an “employee” under the FLSA: economic realities.

It’s the reality, not what we call it, that matters here. Your job title can’t tell you whether or not you’re an independent contractor. Only the reality of the work you perform can do that.

In its new document, the DOL explained a six-part test that can help you determine whether or not you’re economically dependent on your employer, and thus an employee, or in business for yourself, an independent contractor.

1. Is Your Work Integral To An Employer’s Business?

The more dependent an employer is on your labor, the more likely it is that you’re economically dependent on them. At least that’s the logic behind this first question.

In the words of the Department of Labor, “a true independent contractor’s work […] is unlikely to be integral to the employer’s business.”

Here’s an example provided by the new DOL guidance:

A construction company specializes in framing homes. Carpenters, obviously, are integral to putting up those frames, and thus integral to the company’s business. It’s likely that any carpenters working on a project for that company should be classified as employees.

But say the same construction company contracts with a software developer and asks her to design a program that can help track lumber orders and worker scheduling. Is she an employee? Probably not. While tracking orders and scheduling more efficiently will certainly improve the company’s operations, it’s not integral to the business, which remains framing houses.

Workers can be integral and still be interchangeable. In a call center that employs thousands of different customer service representatives, who all do basically the same thing, each representative is considered “integral,” because the company itself is in the business of handling calls.

2. Does Your “Managerial Skill” Affect Your “Opportunity For Profit Or Loss”?

A big part of being economically independent, and thus an independent contractor, is that your decisions affect whether you make or lose money. But this standard could be applied to a lot of employees, too: an employee who chooses to pick up more hours, and makes more money as a result, is still an employee.

So the FLSA focuses on “managerial skill” and true losses.

Managerial activities encompass things like hiring other workers to help you on a job, purchasing equipment and advertising your services. Many true independent contractors essentially run their own businesses, negotiating contracts and seeking out new clients.

But it’s more important that how well you do those things can affect your chances at making a profit or suffering a loss.

By choosing carefully which materials to purchase for a project, you can cut your expenses and make a bigger profit. By the same token, if you do a great job and come in under budget, your current client may recommend your services to someone else, increasing your opportunities for profit in the future. At the same time, you risk a future loss of opportunity if you do a poor job now.

This is a loss of investment, maybe of time, maybe of capital, not a loss in wages. Employees can lose the opportunity for more wages by doing poor work and having their hours cut, but they’re still employees.

3. How Does Your Investment Compare Relative To An Employer’s Investment?

Are you investing as much, or close to as much, in the project as the person who hired you? Beyond this particular project, have you invested much in your own opportunities for profit or loss? If so, you may be an independent contractor.

Buying tools, one of the most common justifications for misclassifying an employee as an independent contractor, isn’t enough. Here’s another example from the Department of Labor:

A worker cleans for a local cleaning company. Every year, he receives a 1099 form and his contract classifies him as an independent contractor. But the cleaning company has purchased the company van that he drives to work, buys insurance and almost all of the equipment that he uses. Sometimes, he likes to bring a special cleaning supply to a job, but usually, he doesn’t.

Obviously, the cleaner’s investment, relative to those made by the cleaning company, is extremely small. He’s very likely an employee.

Another cleaner bought their own van for work travel, all of the supplies to clean with, advertises her services to new clients and even hires extra helpers for big jobs. Sometimes, she works for another cleaning company, but she’s also out there trying to drum up her own business.

Relative to the cleaning company she occasionally works for, the second cleaner has made a similar investment. She’s probably an independent contractor.

4. Does Your Work Require “Special Skill & Initiative”?

In this question, we’re really talking about business skills, not technical ones. Carpenters and electricians, while certainly skilled and often classified as independent contractors, may not be exercising independent judgment and initiative on the job.

In other words, providing skilled labor to an employer isn’t enough to make you an independent contractor. It’s more about looking past this job to the next one.

For example:

Imagine two carpenters. Both are highly-skilled.

One provides his services to a construction firm, but his skills aren’t really used in an independent manner. On the job site, he makes decisions that pertain to the task at hand, but he’s not thinking about ordering new materials or lining up the next project. His employer tells him when to show up and what to do when he gets there. He’s most likely an employee.

The other carpenter crafts custom cabinets for a number of local construction companies. But his real business skill comes in handy when he needs to decide which orders to fill first, when to buy new materials and how best to market his skills to potential clients. He’s probably an independent contractor.

5. Is Your Relationship To An Employer “Permanent Or Indefinite”?

Workers who stay with the same employer until they quit or get fired are likely employees. Independent contractors, on the other hand, generally want a definite end-point for the working relationship, since they’re looking for the next client.

Some industries have a lack of permanence built-in. Agricultural businesses rely on seasonal workers, many of whom are migrant, moving from one part of the country to another. But this doesn’t necessarily make them independent contractors because they’re movements are intrinsic to the nature of farm labor.

If you’re an independent contractor, the lack of permanence in your work relationship’s is due to your own business initiative.

6. What Is The Nature & Degree Of An Employer’s Control?

The Department of Labor’s new presentation of the economic realities test didn’t jettison “control” entirely.

Do you control meaningful aspects of the work you do? Do you have enough control over what you do and how you do it that someone else would think you were running your own business? If yes, you may be an independent contractor.

But this doesn’t have much to do with where or when you work. In the contemporary economy, many of us work from home and make our own hours. Most of us are still employees.

The DOL’s new guidance provides a nice example of the distinction:

Take two registered nurses. Both provide skilled care in nursing homes. Both are registered with Nurse Registries who link them with clients.

One was interviewed before joining the Registry and had to do training sessions with the company before being matched with nursing homes. The Registry sends her a list of potential clients every week, but she has to notify the company before calling anyone. She has to tell the Registry if she gets hired and has to remain within a predetermined wage range. She’s probably an employee.

The other nurse receives a weekly list of potential clients, but he can choose to call whoever he wants. He’s also allowed to set his own wage and schedule his hours with the nursing home independent of the Registry. He’s most likely an independent contractor.

Now that we’ve run through the six-step economic realities test, note that none of these questions matter any more than the others. Each of your answers should be used as a guide to help you determine whether or not you’re economically dependent on an employer.

If you are, the Fair Labor Standards Act protects you. Most employees are guaranteed a minimum wage of at least $7.25 per hour and overtime pay at one-and-a-half their regular rate for any hours worked over 40 in a week.

Very Knowledgeable! Wage Advocates were extremely helpful. They are true professionals!"Rating: 5.0 ★★★★★