Many American workers are shocked to learn that they’ve been underpaid for weeks, months or even years.

Many American workers are shocked to learn that they’ve been underpaid for weeks, months or even years.

The Fair Labor Standards Act, or FLSA, affords the majority of US employees numerous protections, entitling many to a Federal minimum wage and fair overtime pay.

But every year, hundreds of thousands of workers learn that their employers aren’t playing fair, literally cheating hard-working individuals and families out of the very money they’ve earned.

Violating The FLSA: 6 Ways Employers Illegally Cut Into Wages

Knowing your rights under the FLSA is essential, but recognizing a federal wage violation can still be difficult.

Below you’ll find 6 of the most common wage violations explained. To jump directly to a specific violation, follow one of these links:

- Working “Off The Clock”: Failing To Track Work Hours

- Employee Misclassification

- Misclassifying Employees As Independent Contractors

- Inaccurate Hour Tracking: “Chinese Overtime,” Time Clocks & Averaging Workweeks

- Charging Minimum Wage Employees For Certain Expenses

- Failing To Count Certain Bonuses As Wages

1. Working “Off The Clock”: When Employers Fail To Count Hours Worked

What is an “employee”?

According to the FLSA, the definition of employment includes “to suffer or permit to work.” In other words, “work” is more than just the tasks an employer tells an employee to do; the concept also includes all the tasks that an employer allows an employee to perform, so long as the employer has reason to believe that they will benefit from the work being done.

long as the employer has reason to believe that they will benefit from the work being done.

If a worker performs tasks beyond those explicitly delegated by their employer, and the employer “permits” them to do so (even if that means not saying anything), those tasks count towards the employee’s hours worked. Usually, this means that an employer can’t require that you receive permission before working overtime.

If an employer knows, or has reason to know, that you’re working over, those hours count toward overtime.

Coming in early to get ready for work, staying late to finish something up, working late to meet a deadline and working through part or all of a meal break (even ones that are usually uncompensated): they all count toward hours worked. The majority of unpaid overtime lawsuits filed by call center workers involve uncompensated pre- and post-shift work duties.

Some of the most common wage violations fall into this category:

Waiting Around: Sometimes It’s Part Of Your Job

Employers often fail to pay employees for “waiting time.” But some “waiting” isn’t considered work under the FLSA. The real distinction comes down to whether or not an employee has been “engaged” to wait.

For example, an administrative assistant waiting for a phone call who checks their Facebook or reads a magazine is still working. This employee has been “engaged to wait”; it’s a fundamental part of their job.

The text of the FLSA provides some more examples: a “fireman [or woman] who plays checkers while waiting for alarms and a factory worker who talks to his [or her] fellow employees while waiting for machinery to be repaired are all working during their periods of inactivity.” Waiting time like this counts toward overtime.

The text of the FLSA provides some more examples: a “fireman [or woman] who plays checkers while waiting for alarms and a factory worker who talks to his [or her] fellow employees while waiting for machinery to be repaired are all working during their periods of inactivity.” Waiting time like this counts toward overtime.

“Waiting to be engaged” is a different story.

Take another example from the FLSA: a truck driver sets out at 6 am and delivers his goods in a different city at noon. For the next six hours, he’s relieved from duty. While he has to set out for another State at 6 pm tonight, these six hours are his and he can do what he wants.

The fact that the truck driver can occupy this period as he pleases is integral to the question of whether he has been “engaged to wait” or is “waiting to be engaged.”

For our administrative assistant, the phone could ring at any time. Our firefighter’s game of checkers could be interrupted by an alarm in the next minute. Under the FLSA, their idle time belongs to an employer because there’s no guarantee that they’ll be able to effectively use the time for their own purposes. Since the truck driver has such a guarantee, his waiting hours do not count towards overtime.

If you can reasonably believe that your time is being spent for your employer’s benefit, that’s most likely work. With that being said, employers can always set rules, and prohibit “off the clock” work, but they have to enforce them.

Commuting & Work Travel

In most cases, commuting to and from work does not count as hours worked. But this changes depending on what you’re required to do in your commute. If your employer needs you to pick up other employees and drive them to work, this may count toward your hours. Getting work supplies at a store, or picking up supplies at the office on the way to another site, probably count too.

Unlike driving from home to work, traveling to and from job sites counts toward hours worked. “Job site” in this instance includes places you need to go for supplies, or perform other work-related duties.

Unlike driving from home to work, traveling to and from job sites counts toward hours worked. “Job site” in this instance includes places you need to go for supplies, or perform other work-related duties.

If you’re required to stop in a work-related capacity during your daily commute, some of your commute becomes hours worked. For example, you drive 20 minutes from home to work every morning. One day, your employer asks you to pick up some supplies from a store 5 minutes away from your house. The 15 minutes of driving it takes you to get from that store to work counts as hours worked.

Company vehicles might also matter. If you drive a company vehicle that isn’t normally used by commuters, like a big truck that prevents you from taking certain roads, or one that requires you to take on additional expenses (like an additional toll), this may be considered work time.

If you usually commute to a single office, but need to drive a substantial distance one day for a special assignment, most of this unusual commute should be counted as hours worked. Your employer is allowed to subtract however long your normal commute is from this new travel time.

Let’s say you travel for work and your travel keeps you away from home overnight. You have a flight on Monday, and while you might not be able to do any work on the plane, the time you spend on the plane during your normal workday hours is still considered work.

So if you usually work from 8 am to 6 pm, and your flight lasts from 9 am to 2 pm, those five hours count toward hours worked. If, on the other hand, the flight goes from 4 pm to 8 pm, only the two hours of travel prior to 6 pm likely count as work. This also applies to non-working days, but again, only during your normal working hours (there may be some exception if you’re driving).

If you get called back to work after leaving for the day, that driving time might be counted toward your hours, depending on how far you have to go.

Working “On-Call”

Some hospital employees are required to remain “on-call”; many facilities even feature “on-call” rooms in which employees can chat, watch TV, read books or sleep.

But in the vast majority of cases, these employees are not allowed to leave the premises. This is a “constraint” on their freedom, required in the course of their employment, and means that “idle” hours spent on-call count towards hours worked.

But in the vast majority of cases, these employees are not allowed to leave the premises. This is a “constraint” on their freedom, required in the course of their employment, and means that “idle” hours spent on-call count towards hours worked.

To learn more about other common wage violations involving hospital employees, click here.

Other workers may need to be on-call, but aren’t confined to the workplace. If you can go home, but expect a call later and leave a number where people can reach you, you’re probably not working on-call by the FLSA’s definition. But this distinction also depends on how often your time away from the workplace will be interrupted.

Generally, if you’re receiving so many calls, no matter where you are, that you can’t get anything personal done, your on-call time should count as hours worked. If you have time to mow the lawn, or enjoy a meal, you’re probably not on-call.

Taking Breaks

Short breaks, no longer than 20 minutes in most cases, count towards hours worked.

If you go out for a 15 minute break and return 2 hours later, your time away might not count toward overtime wages. But for this exception to be ironclad, your employer has to unambiguously state that your break should last for a defined period of time, that leaving for longer is against the rules, and that you can be punished for breaking those rules.

If you go out for a 15 minute break and return 2 hours later, your time away might not count toward overtime wages. But for this exception to be ironclad, your employer has to unambiguously state that your break should last for a defined period of time, that leaving for longer is against the rules, and that you can be punished for breaking those rules.

As a subset of breaks, time taken for meals (in most cases 30 minutes or longer) does not usually need to count toward your hours worked. But for this to be true, you have to be completely free of duty. For example, if you’re expected to answer calls during your meal, this time counts toward your hours.

Your employer is responsible for ensuring that you’re completely relieved of duty during a meal break. This almost never happens in the health care industry. Hourly nurses are chronically uncompensated for the breaks they work through.

“Rework”: Getting The Job Done Right

If you have to go back to old work and fix mistakes, either someone else’s or your own, you’re working and that time counts toward your hours. This is true even if you stay late of your own volition.

After A Shift

Time spent performing activities at the workplace after your workday is complete are not considered hours worked if they’re primarily for your own benefit.

![]() An example could be taking a shower in the company lockers: since it’s not necessary to your employment that you return home clean, the 20 or so minutes it takes to shower are not hours worked. Performed before your workday begins, activities like taking a shower at the workplace aren’t usually counted as time worked either.

An example could be taking a shower in the company lockers: since it’s not necessary to your employment that you return home clean, the 20 or so minutes it takes to shower are not hours worked. Performed before your workday begins, activities like taking a shower at the workplace aren’t usually counted as time worked either.

There may be exceptions to this rule, if you (or your representative) have a written or unwritten contract with your employer that those activities count as hours worked, or if those hours customarily count toward work hours at your workplace.

2. Employee Misclassification

Under the FLSA, certain types of employees are exempt from the Act’s minimum wage and overtime pay requirements. Other types of workers are exempted from the FLSA’s overtime provisions, but not the minimum wage rules.

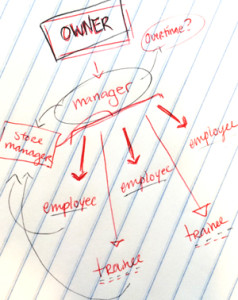

An extremely common wage violation involves employers misclassifying their workers as one of these exempt categories: managers (or “executives”), professionals or administrators. To find a detailed overview of these categories, and criteria that can help you determine if you fit into one, click here.

An extremely common wage violation involves employers misclassifying their workers as one of these exempt categories: managers (or “executives”), professionals or administrators. To find a detailed overview of these categories, and criteria that can help you determine if you fit into one, click here.

Being a manager, professional or administrator is not the same as having a job title that describes you as one of those things. In other words, not every “store manager” is a manager under the FLSA’s definitions. In fact most “managers” at retail stores are entitled to overtime pay.

Being exempt from the Act’s overtime provisions depends not on what you are called, but on what you do, on what your actual job duties are.

A concrete example might help explain this: Paul is a cashier at a small grocery store. Suddenly, he receives a promotion and becomes the store’s “assistant manager.” He still works the register, stocks shelves and cleans up at night. In fact, none of his duties have changed at all. Is Paul now exempt from overtime pay? No.

To be a manager, Paul needs to manage. He would need to supervise multiple employees on a regular basis and have a constructive impact on personnel decisions, like hiring and firing. Paul deserves overtime pay, and under the FLSA, he’s entitled to it.

Who Gets Misclassified The Most?

Some types of employees seem to exist in a “gray area.” They appear close to one of the exempt categories, and are thus more likely to be misclassified than others:

Accountants and bookkeepers without CPAs

Accountants and bookkeepers are often mathematically-minded people, who perform largely “intellectual” work, which makes it seem like they fall under the FLSA’s “professional” category. But in most cases, an advanced degree or professional certification is required for that designation.

Computer techs and network administrators who don’t write much code

Like accountants, computer technicians usually only fall under the FLSA’s “learned professional” category if they have earned advanced degrees in their field.

Warehouse foremen and clerical workers

Employees in warehouses, which sell goods for resale rather than to end consumers, are often misclassified as “administrators” or “executives.”

Nurses and licensed practical nurses (LPN)

Chronically misclassified as exempt “professionals,” most licensed practical nurses are entitled to overtime. Registered nurses may or may not be, depending on their level of “advanced knowledge” in a medical field, whether or not they receive a salary no less than $455 per week and the primary tasks of their employment.

Both confusing and improving the matter, the Department of Labor’s guidelines on employee classification are always changing. A recent shift in the agency’s philosophy extended overtime protections to thousands of home health aides who used to be exempt.

Wage and hour violations are also particularly prevalent in restaurants.

3. Classifying Employees As Independent Contractors

Misclassifying employees as “independent contractors” is one of the greatest challenges facing US regulators today. As more and more businesses opt to contract out parts of their operations, understanding the legal difference between an employee and a true independent contractor is more important than ever.

Most “employees” are entitled to the FLSA’s minimum wage (or an applicable State’s wage) and overtime regulations, while truly “independent” contractors aren’t. The distinction here is nuanced and depends on what the Act calls “economic realities,” rather than a worker’s official title.

In a general sense, “employees” are financially dependent on their employer’s business. Most workers count as employees, and non-exempt employees are entitled to all of the FLSA’s protections.

Independent contractors, on the other hand, are financially independent from whichever business they happen to be working for at the time; they are “in business for themselves,” as the Department of Labor says.

The Economic Realities Test

Despite the title of this section, there is no one test that can conclusively distinguish between an independent contractor and an employee for every working relationship. This was the US Supreme Court’s ultimate decision in United States v. Silk, 331 U.S. 704 (1947), but the Court outlined six considerations that can help determine whether or not a worker is “economically dependent” on an employer:

Does an employer depend on your work?

The more integral your work is to an employer’s business, the more likely you are to be an employee. For example, if you perform an essential task in the manufacture of some product that your employer sells, you’re probably integral to the business.

Is your work relationship permanent?

The permanence of a work relationship may go some way to suggest that a worker is truly an employee, even when the term of employment is simply undefined. But some employees have impermanent relationships with their employers, too, like those working in industries that are shrinking.

Are you in it for yourself?

Do you exercise “independent business judgment”? For example, are you a skilled laborer competing with others for work? If so, you may be operating more like an independent business, and working for “employers” who are more like clients. You’re not truly dependent on one employer, because you may have other clients to fall back on if you lose a job.

Are you invested in the business?

Employers invest in their businesses, buying equipment and hiring staff. In doing so, they take on substantial risks: if the business fails, they’re likely to lose much of their investments. In the Supreme Court’s eyes, independent contractors do, too. But buying tools isn’t enough. The amounts of investment made by an employer and a true independent contractor must be equivalent enough to suggest that they both share the risk of the business’ losses.

Who controls the work relationship?

Who sets your wages or salary? Who decides how the work is to be done? Who is allowed to hire more people for the job? If your answer to these questions is your employer, you’re probably an employee. This is a question of control. Employers generally control the work environment and conditions of employment for employees, while independent contractors are allowed significantly more freedom. Note that this is a nuanced issue, and many people who work under minimal employer control can still be considered employees.

Since employers are not required to pay their portion of Social Security, Medicare and State unemployment tax, let alone offer benefits, to independent contractors, misclassifying an employee can be extremely lucrative.

According to the US General Accounting Office, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) helped 527,000 workers misclassified as independent contractors, and sought to collect more than $830 million in unpaid taxes from their employers, between 1988 and 1995.

With the rise of “networking” companies, like Uber, who say they only offer online marketplaces through which independent service providers can find jobs, more workers than ever are being thrown into a gray area between employee and independent contractor. FedEx recently settled a class action for $228 million, over allegations that the company had misclassified more than 2,000 delivery drivers as independent contractors. Numerous major players within the so-called “sharing economy,” including Uber, Caviar and DoorDash, have been hit with wage violation lawsuits in recent months.

4. Inaccurate Hour Tracking

Many workplaces use time clocks to efficiently track employee hours. Early clock-ins and late clock-outs usually don’t need to be counted toward work hours, so long as an employee doesn’t perform any work before or after their regular starting or closing time.

In the event that you do work before or after the customary endpoints of your workday, that time counts.

The FLSA accepts that minor discrepancies between a worker’s clocked hours and the hours that actually count towards work are usually unavoidable, but major or chronic discrepancies that do not accurately capture the amount of hours an employee works are likely a violation of the FLSA’s minimum wage and overtime requirements.

Rounding Down

In order to eliminate the discrepancy between a clock-in time and the time an employee actually begins to work, many employers round what the clock has recorded to the nearest 5, 6 or 15 minutes. This practice is acceptable under the FLSA, as long as it “balances out overtime.”

Employers should round both up and down, when appropriate. Generally, the rule of thumb holds that if you clock out anywhere between 6:01 to 6:07, that can be rounded down to 6:00 and not count towards hours worked. But if you clock out between 6:08 and 6:14, the time should be rounded up to 6:15 and counted.

Clocking in may be a little more confusing. Is it okay for an employer to round down your worked hours if you clock in at 7:08 for a shift that begins at 7:00? In this context, rounding down really looks like rounding up, since your employer is counting 7:15 as your actual start time. But in any event, it’s okay as long as your employer fairly handles the opposite situation. If you clock in at 6:52 for that 7:00 shift and your employer rounds those extra minutes up to a full 15 minutes of work time, then the rounding down from when you were a little late has been balanced out.

If your employer always rounds down, it’s likely that your being under compensated for your hours.

A more egregious practice sees employers demanding that workers set up, clean or close down before or after clocking in. This is a blatant violation of the FLSA and an insult to workers.

“Chinese Overtime”: The Fluctuating Workweek

Also known as “half-time” or “half-pay,” “Chinese overtime” is an arrangement in which employees are paid half their regular wage for any hours worked over 40 in a workweek, rather than one-and-a-half times as mandated by the FLSA.

“Chinese overtime” is legal, in certain situations. If an employee works a different amount of hours from week to week, but receives a set salary no matter what, overtime can be paid at one-half their regular wage. For this “fluctuating workweek” arrangement to be lawful, three criteria need to be met:

- Both employer and employee have to unambiguously understand that the set salary covers all hours worked during a workweek, no matter how many hours are actually worked.

- The employee’s hours need to actually change from week to week.

- The employee’s “regular rate,” used to calculate overtime compensation, cannot fall below the federal minimum wage.

That last point can be tricky. Here’s an example:

Claire gets paid a fixed salary of $375 every week. One week she works 45 hours. Her regular rate is how much she made for the workweek divided by how many hours she worked; in this case, around $8.33 and above the federal minimum wage of $7.25. Her employer can lawfully pay her for five hours of overtime at a rate of $4, half her regular rate.

Claire gets paid a fixed salary of $375 every week. One week she works 45 hours. Her regular rate is how much she made for the workweek divided by how many hours she worked; in this case, around $8.33 and above the federal minimum wage of $7.25. Her employer can lawfully pay her for five hours of overtime at a rate of $4, half her regular rate.

But the next week, Claire is swamped with work and ends up working for 60 hours. Her regular rate for this period is $6.25 and below the minimum wage. Her employer can’t claim that she is a “fluctuating workweek” employee, and has to pay her overtime according to the FLSA’s regulations: one-and-a-half her regular rate.

In addition, Claire’s employer may be liable for violating the FLSA’s minimum wage requirements, over and above the Act’s overtime requirements.

Averaging Workweeks

For the purposes of calculating overtime, each 40-hour workweek stands alone. Employers are not allowed to add or average multiple workweeks together to get around this.

Since many employees are paid biweekly, it might seem like each work period is actually two weeks, encompassing a total of 80 hours. But that’s not true.

Since many employees are paid biweekly, it might seem like each work period is actually two weeks, encompassing a total of 80 hours. But that’s not true.

Let’s say Paula is paid biweekly. The first week she works 42 hours, and the next she works 38. Adding these two weeks together, her employer John sees that she’s worked exactly 80 hours and doesn’t pay her any overtime, breaking the law in the process. John should have paid Paula overtime for two hours at one-and-a-half times her regular rate for the first week.

5. Unlawfully Charging Employees For Certain Expenses

While employers can make their employees purchase certain necessary work-related items, like uniforms, they are not allowed to reduce a worker’s wage below the minimum or reduce the amount of overtime compensation mandated by the FLSA.

![]() Asking a minimum wage employee to pay for an item in cash is considered a way of getting around the FLSA’s minimum wage requirements and unlawful.

Asking a minimum wage employee to pay for an item in cash is considered a way of getting around the FLSA’s minimum wage requirements and unlawful.

For employees making the minimum wage (the Federal minimum is $7.25 per hour), employers cannot force workers to pay for a business-related expense on their own. Nor can an employer reduce a worker’s rate below the minimum wage for a designated period of time to cover the expense.

This is lawful, on the other hand, for employees making more than the statutory minimum wage. If an employee (one living in a State where the Federal minimum applies) makes $8.00 an hour, $0.75 over the minimum wage, and works a 40-hour workweek, the most an employer could deduct from their wages would be $30 on the week.

Beyond uniforms, any item that is required primarily for the convenience of an employer is subject to this regulation.

6. Bonuses & Gifts: What Counts Toward Overtime?

Under the FLSA, there are two types of bonuses: discretionary and non-discretionary.

Non-discretionary bonuses are awarded to employees who meet certain requirements, generally defined by the employer. A bonus for perfect attendance, or meeting a certain efficiency goal are examples. Any payment over and above an employee’s base wage that is offered because of an accomplished goal counts toward the worker’s “regular rate,” their true hourly wage. This is important because employers use an employee’s “regular rate” to calculate overtime wages.

If an employer awards a “non-discretionary” bonus but doesn’t count that amount towards the calculation of an employee’s overtime compensation, they’ve violated the FLSA.

“Discretionary” bonuses are considered true gifts; they “come out of the blue” and don’t count towards an employee’s regular rate. Expectation is important here. Since many employees expect to receive a Christmas bonus, those payments may be considered “non-discretionary,” even in cases when an employer never made any promise to give one in the first place.

Wonderful to work with! Thank you to Wage Advocates for helping me during a very difficult time in my life!"Rating: 5.0 ★★★★★